- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: -

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: Italy, Italia, Italie

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: 1859-1926

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: -

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Italy, Italia, Italie

- Internet: Visit Website

- Wikidata: Visit Website

- Additional references-Riferimenti complementari-Références complémentaires: Bertarelli, L. V. Insoliti Viaggi: L’appassionante Diario Di Un Precursore. 1. ed. Reportage 1900. Reportage 1900. Milano: Touring club italiano, 2004.

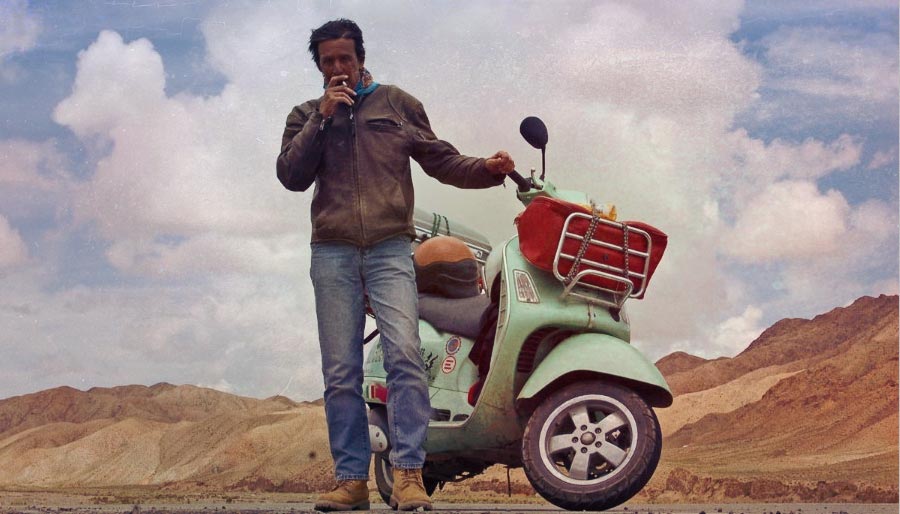

- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: Vespaman

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: Italy, Italia, Italie

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: 1955-2008

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: Vespa

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Around the World, Giro del mondo, Tour du monde

- Internet: Visit Website

- Wikidata: Visit Website

- Additional references-Riferimenti complementari-Références complémentaires: Bettinelli G., In Vespa, Da Roma a Saigon, Milano: Feltrinelli, 2003.

La notizia arrivata dal Sud della Cina ha colpito improvvisamente tutto il grande "popolo dei viaggiatori": il 16 settembre ci ha lasciati Giorgio Bettinelli, vinto da un'infezione sulle rive del Mekong. Giorgio, meglio conosciuto come lo Scrittore-in-Vespa e spesso affettuosamente soprannominato "Vespista per Caso" era forse uno degli ultimi grandi avventurieri-esploratori esistenti, quelli che - per intenderci - fanno del viaggio la missione della propria vita e trovano realizzazione nell'incontro con altri popoli, culture e luoghi.

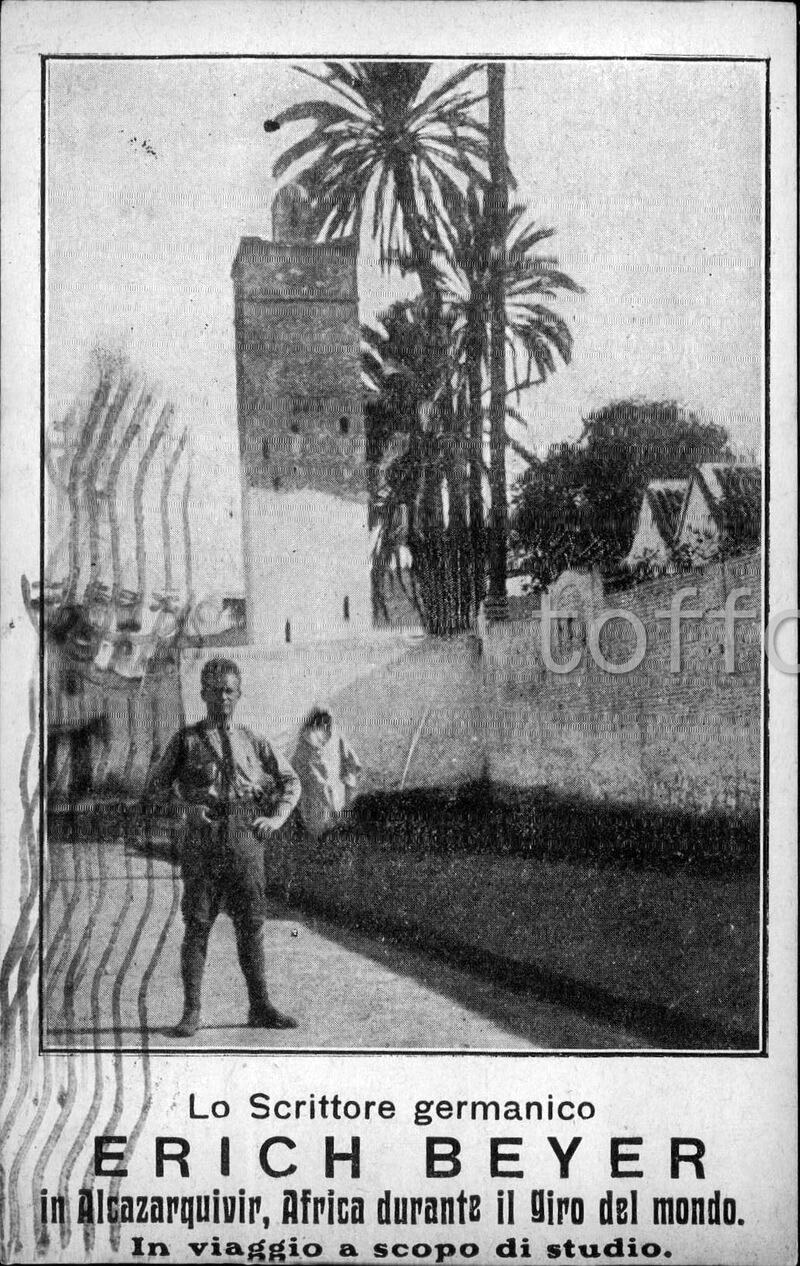

- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: -

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: Germany, Germania, Allemagne

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: -

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: -

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Around the World, Giro del mondo, Tour du monde

- Inscriptions-Iscrizioni-Inscriptions: Lo scrittore germanico. In viaggio a scopo di studio

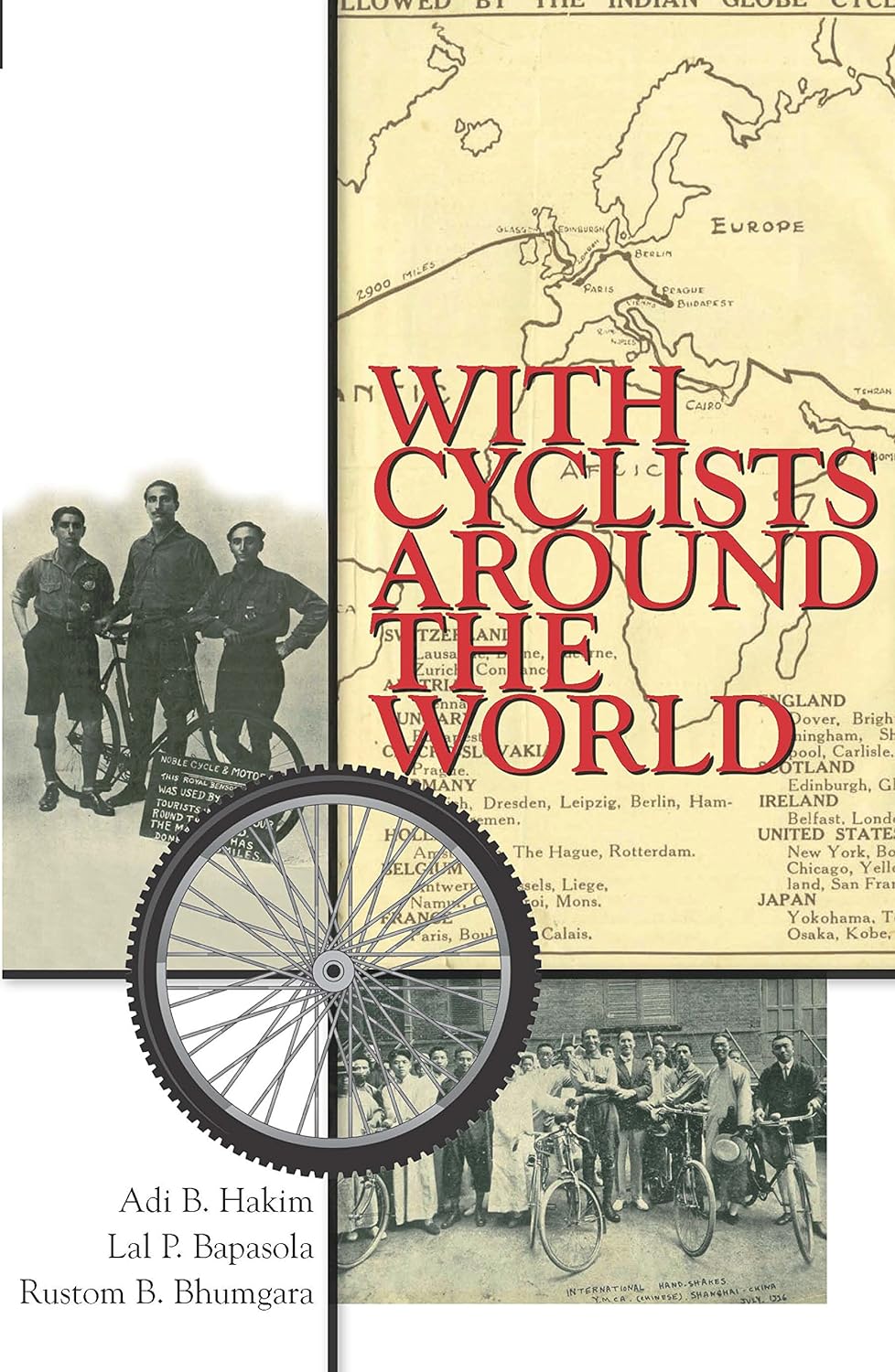

- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: -

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: India

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: -

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: Bike, tricycle, Bicicletta, triciclo, Vélo, tricycle

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Around the World, Giro del mondo, Tour du monde

- Inscriptions-Iscrizioni-Inscriptions: Noble cycle & motor Co. - This Royal bassett (?) bicycle was used by the world tourists in their tour round the world. The machine has done 40.000 miles

Just in their twenties and living off a shoestring budget, three young Parsis, one from Baroda, ventured on the first ever trip around the world on bicycles on October 15, 1923. The trio covered 44,000 miles in three years and three months across 27 countries and four continents. On their return, Adi Hakim from Vadodara, Jal Bapasola from Mumbai and Rustom Bhumgara from Pune, who later became a freedom fighter, wrote a book of their memoirs from the epic journey, of which but a few copies still exist. The original book includes a foreword by Jawarharlal Nehru and comments from leaders around the world like Benito Mussolini and Calvin Coolidge.”

- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: -

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: USA

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: -

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: Bike, tricycle, Bicicletta, triciclo, Vélo, tricycle

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Around the World, Giro del mondo, Tour du monde

- Internet: Visit Website

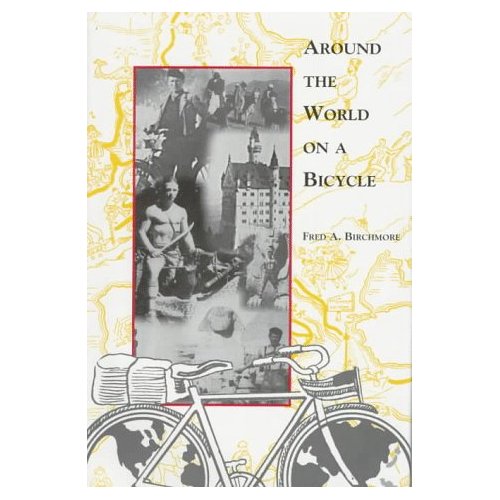

- Additional references-Riferimenti complementari-Références complémentaires: Birchmore F. A., Around the world on a bicycle, Cucumber Island Storytellers, 1996.

Fred Birchmore’s Amazing Bicycle Trip Around the World. The American cyclist crossed paths with Sonja Henje and Adolf Hitler as he transversed the globe on Bucephalus, his trusty bike

- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: -

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: UK, Inglese, Anglais

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: 1831-1904

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: Various, Diversi, Différents

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Various, Diversi, Différents

- Internet: Visit Website

- Wikidata: Visit Website

- Additional references-Riferimenti complementari-Références complémentaires: Bird I., Isabella Bird, Una lady nel West : tra pionieri, serpenti e banditi sulle Montagne Rocciose, EDT, 1998. Scatamacchia C., Nellie Bly: Un'avventurosa giornalista e viaggiatrice americana dell'Ottocento, Perugia : Morlacchi Editore, 2002.

Life of a Victorian adventuress: Incredible story of clergyman's daughter who braved malaria, floods and wars to trek across China

- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: -

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: Australia

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: 1881-1941

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: Various, Diversi, Différents

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Around the World, Giro del mondo, Tour du monde

- Internet: Visit Website

- Wikidata: Visit Website

- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: B.L.R. Dane

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: USA

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: 1861-1929

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: Various, Diversi, Différents

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Around the World, Giro del mondo, Tour du monde

- Internet: Visit Website

- Wikidata: Visit Website

- Additional references-Riferimenti complementari-Références complémentaires: Bisland E., A Flying Trip Around The World, 1891. Marks J., Around the World in 72 Days: The race between Pulitzer's Nellie Bly and Cosmopolitan's Elizabeth Bisland, Gemittarius Press, 1993.

If, on the 13th of November, 1889, some amateur prophet had foretold that I should spend Christmas Day of that year in the Indian Ocean, I hope I should not by any open and insulting incredulity have added new burdens to the trials of a hard-working soothsayer – I hope I should, with the gentleness due a severe case of aberrated predictiveness, have merely called his attention to that passage in the Koran in which it is written, "The Lord loveth a cheerful liar" – and bid him go in peace. Yet I did spend the 25th day of December steaming through the waters that wash the shores of the Indian Empire, and did do other things equally preposterous, of which I would not have believed myself capable if forewarned of them. I can only claim in excuse that these vagaries were unpremeditated, for the prophets neglected their opportunity and I received no augury.

- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: -

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: France, Francia

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: -

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: On foot, A piedi, A pied

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Around the World, Giro del mondo, Tour du monde

- Internet: Visit Website

- Multimedia: https://www.youtube.com/@toutenmarchant

If you happen to see two backpack-toting white men doing some serious walking, chances are they are the globe-trotting French guys who have been walking for the past six years in a journey of a lifetime through many countries that has now brought them to Malaysia.

- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: -

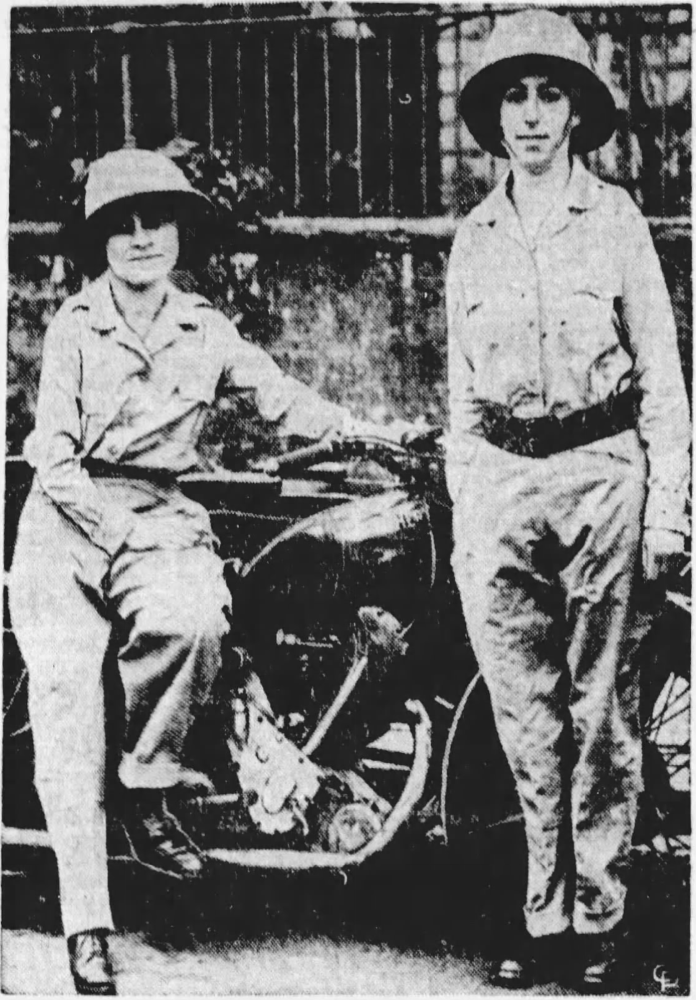

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: UK, Inglese, Anglais

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: 1904-1991

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: Motorbike, Motocicletta, Moto

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Africa

- Internet: Visit Website

- Wikidata: Visit Website

- Additional references-Riferimenti complementari-Références complémentaires: Wallach, Teresa. The Rugged Road : Due Donne E Una Moto, Da Londra a Città Del Capo. Roma: Ultra, 2014

- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: -

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: -

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: -

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: On foot, A piedi, A pied

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Around the World, Giro del mondo, Tour du monde

- Internet: Visit Website

- Wikidata: Visit Website

- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: The man of steel

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: -

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: 1940-

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: Boat, ship, Barca, nave, Bateau

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Around the World, Giro del mondo, Tour du monde

- Internet: Visit Website

- Wikidata: Visit Website

- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: -

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: Switzerland, Svizzera, Suisse

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: -

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: Bike, tricycle, Bicicletta, triciclo, Vélo, tricycle

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Silk Road, Via della seta, Route de la soie

- Additional references-Riferimenti complementari-Références complémentaires: Bolliger S., Perrin A., Sulla Via della Seta, La Città, luglio 2008.

Sono partiti. Sono montati in sella alla loro bicicletta e hanno iniziato il loro percorso che li porterà a visitare diversi paesi, fino ad arrivare in India.

- Alias-Pseudonimo-Pseudonyme: -

- Nationality-Nazionalità-Nationalité: Switzerland, Svizzera, Suisse

- Birth/death-Nascita/morte-Naissance/mort: 1971-

- Means of transport-Mezzo di trasporto-Moyen de transport: Bike, tricycle, Bicicletta, triciclo, Vélo, tricycle

- Geographical description-Riferimento geografico-Référence géographique: Around the World, Giro del mondo, Tour du monde

.jpg)

Italiano

Italiano  Français

Français  Deutsch

Deutsch  English

English