When dinner was served I went in very bravely and took my place on the Captain's left. I had a very strong determination to resist my impulses, but yet, in the bottom of my heart was a little faint feeling that I had found something even stronger than my will power.

Dinner began very pleasantly. The waiters moved about noiselessly, the band played an overture, Captain Albers, handsome and genial, took his place at the head, and the passengers who were seated at his table began dinner with a relish equaled only by enthusiastic wheelmen when roads are fine. I was the only one at the Captain's table who might be called an amateur sailor. I was bitterly conscious of this fact. So were the others.

I might as well confess it, while soup was being served, I was lost in painful thoughts and filled with a sickening fear. I felt that everything was just as pleasant as an unexpected gift on Christmas, and I endeavored to listen to the enthusiastic remarks about the music made by my companions, but my thoughts were on a topic that would not bear discussion.

I felt cold, I felt warm; I felt that I should not get hungry if I did not see food for seven days; in fact, I had a great, longing desire not to see it, nor to smell it, nor to eat of it, until I could reach land or a better understanding with myself.

Fish was served, and Captain Albers was in the midst of a good story when I felt I had more than I could endure.

"Excuse me," I whispered faintly, and then rushed, madly, blindly out. I was assisted to a secluded spot where a little reflection and a little unbridling of pent up emotion restored me to such a courageous state that I determined to take the Captain's advice and return to my unfinished dinner.

"The only way to conquer sea-sickness is by forcing one's self to eat," the Captain said, and I thought the remedy harmless enough to test.

They congratulated me on my return. I had a shamed feeling that I was going to misbehave again, but I tried to hide the fact from them. It came soon, and I disappeared at the same rate of speed as before.

Once again I returned. This time my nerves felt a little unsteady and my belief in my determination was weakening, Hardly had I seated myself when I caught an amused gleam of a steward's eye, which made me bury my face in my handkerchief and choke before I reached the limits of the dining hall.

The bravos with which they kindly greeted my third return to the table almost threatened to make me lose my bearings again. I was glad to know that dinner was just finished and I had the boldness to say that it was very good!

Bly, Nellie. Around the World in Seventy-Two Days. New York: The Pictorial Weeklies Company, 1890.

We went down to dinner, and only the fact of not having tasted food for many hours could have made me touch it in such a room. We were in a long apartment, with one table down the middle, with plates laid for one hundred people. Every seat was occupied, these seats being benches of somewhat uncouth workmanship. The floor had recently been washed, and emitted a damp fetid odour. At one side was a large fireplace, where, in spite of the heat of the day, sundry manipulations were going on, coming under the general name of cookery. At the end of the room was a long leaden trough or sink, where three greasy scullery-boys without shoes, were perpetually engaged in washing plates, which they wiped upon their aprons. The plates, however, were not washed, only superficially rinsed. There were four brigand-looking waiters with prodigious beards and moustachios.

There was no great variety at table. There were eight boiled legs of mutton, nearly raw; six antiquated fowls, whose legs were of the consistence of guitar-strings; baked pork with "onion fixings," the meat swimming in grease; and for vegetables, yams, corn-cobs, and squash. A cup of stewed tea, sweetened with molasses, stood by each plate, and no fermented liquor of any description was consumed by the company. There were no carving-knives, so each person hacked the joints with his own, and some of those present carved them dexterously with bowie-knives taken out of their belts. Neither were there salt-spoons, so everybody dipped his greasy knife into the little pewter pot containing salt. Dinner began, and after satisfying my own hunger with the least objectionable dish, namely "pork with onion fixings," I had leisure to look round me.

Bird, Isabella. The Englishwoman in America, 1856.

In nessuna

parte

di terra

mi posso

accasare

A ogni

nuovo

clima

che incontro

mi trovo

languente

che

una volta

già gli ero stato

assuefatto

E me ne stacco sempre

straniero

Nascendo

tornato da epoche troppo

vissute

Godere un solo

minuto di vita

iniziale

Cerco un paese

Innocente

Girovago, di Giuseppe Ungaretti, pubblicato nell'opera L'Allegria, 1931

Può sembrare esagerato suggerire a qualcuno di prendere la strada sbagliata, o di perdersi, ma può essere anche un buon consiglio.

‘Mi indicò la strada per Minhead, non la più breve, ma la più bella, disse. Aveva i capelli chiari e gli occhi scuri. Dissi che la sua casa era bella. Lei disse che era una pensione; poi rise. ‘Perché non resta qui stanotte?” Lo diceva sul serio e sembrava tenerci e allora non fui certo di che cosa offrisse. Rimasi lì in piedi e le sorrisi di rimando… Non era nemmeno l’una e non mi ero mai fermato in un luogo così presto. Dissi, ‘Forse una volta tornerò’. ‘Sarò ancora qui’, disse lei.

(Theroux 1983)

Citato in Leed, Eric J. 1992. La mente del viaggiatore: dall’Odissea al turismo globale. Biblioteca storica Il Mulino. Bologna: Il Mulino.

La forza del viaggio è corrosiva, spoglia e consuma; è un’esperienza di perdita continua. Il mondo creato dal viaggio è segnato tanto da ciò che manca quanto da ciò che è presente.

Leed, Eric J. 1992. La mente del viaggiatore: dall’Odissea al turismo globale. Biblioteca storica Il Mulino. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Mi svegliai che il sole si faceva rosso; e quello fu l’unico, chiaro momento della mia vita, il momento più strano di tutti, in cui non seppi chi ero… Mi trovavo lontano da casa, stralunato e stanco del viaggio, in una misera camera d’albergo che non avevo mai vista,… e guardavo l’alto soffitto pieno di crepe e davvero non seppi chi ero per circa quindici strani secondi. Non avevo paura; ero solo qualcun altro, un estraneo, e tutta la mia vita era una vita stregata, la vita di un fantasma. Mi trovavo a metà strada attraverso l’America, alla linea divisoria fra l’Est della mia giovinezza e l’Ovest del mio futuro, ed è forse per questo che ciò accadde proprio lì e in quel momento, in quello strano pomeriggio rosso.

(Jack Kerouac, 1967)

Citato in Leed, Eric J. 1992. La mente del viaggiatore: dall’Odissea al turismo globale. Biblioteca storica Il Mulino. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Travel, in other words, has changed our world and our lives, and in all probability will further shape our lives in the future.

E nacque un altro sentiero hippie, un itinerario che conduceva dall’Olanda, da Amsterdam, fino in Nepal, a Kathmandu. Il biglietto del pullman costava meno di cento dollari e consentiva di percorrere paesi molto interessanti: Turchia, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan e alcune aree dell’India (debitamente lontane dal tempio di Maharishi). Il viaggio durava tre settimane e affrontava un numero considerevole di chilometri.

Coelho, Paulo. Hippie. Milano: La nave di Teseo, 2018.

A new hippie trail was created, from Amsterdam to Kathmandu, on a bus that charged a fare of approximately a hundred dollars and traveled through countries that must have been pretty interesting: Turkey, Lebanon, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and part of India (a great distance from the Maharishi’s temple, it’s worth noting). The trip lasted three weeks and an insane number of miles.

Coelho, Paulo. Hippie. Milano: La nave di Teseo, 2018.

Dopo che tutti gli invitati ebbero ordinato le pietanze, il cameriere si rivolse a Jacques: ‘Il solito?’‘Il solito, sì.’ Ostriche come antipasto, specificando che dovevano essere servite vive - qualcosa che sconcertava la maggior parte dei suoi ospiti stranieri. E poi lumache - le celebri escargots - e, dopo, cosce di rana fritte.Nessuno aveva il coraggio di imitare quella scelta – ed era proprio ciò che voleva. Si trattava una tattica di marketing.Gli antipasti arrivarono quasi subito. Quando vennero servite le ostriche, i commensali lo guardarono. Jacques spremette qualche goccia di limone sul primo mollusco, che scattò si contrasse, suscitando la sorpresa e lo sgomento degli invitati. Poi lo fece scivolare tra le labbra e lo inghiottì, prima di assaporare il liquido salato rimasto nella conchiglia.

Coelho, Paulo. Hippie. Milano: La nave di Teseo, 2018.

The idea of travelling round the world had come to me one day in March that year, out of the blue. It came not as a vague thought or wish but as a fully formed conviction. The moment it struck me I knew it would be done and how I would do it. Why I thought immediately of a motorcycle I cannot say. I did not have a motorcycle, nor even a licence to ride one, yet it was obvious from the start that that was the way to go, and that I could solve the problems involved.

It is no trick to go round the world these days, you can pay a lot of money and fly round it nonstop in less than forty-eight hours, but to know it, to smell it and feel it between your toes you have to crawl. There is no other way. Not flying, not floating. You have to stay on the ground and swallow the bugs as you go. Then the world is immense.

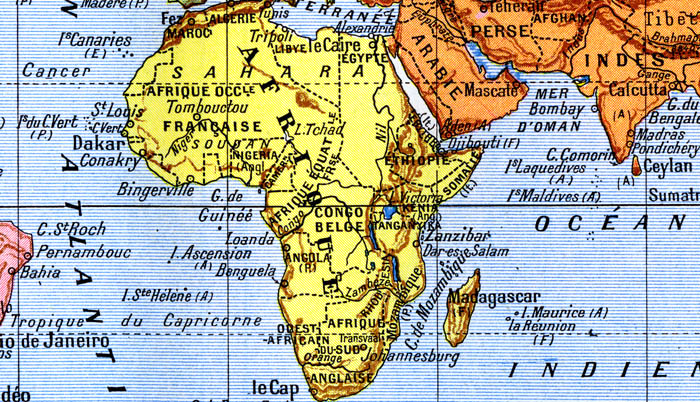

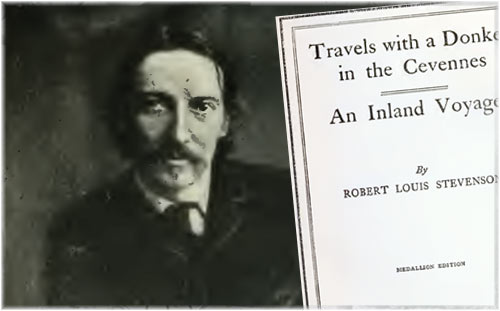

Travel

I should like to rise and go

Where the golden apples grow;-

Where below another sky

Parrot islands anchored lie,

And, watched by cockatoos and goats,

Lonely Crusoes building boats;-

Where in sunshine reaching out

Eastern cities, miles about,

Are with mosque and minaret

Among sandy gardens set,

And the rich goods from near and far

Hang for sale in the bazaar;-

Where the Great Wall round China goes,

And on one side the desert blows,

And with bell and voice and drum,

Cities on the other hum;-

Where are forests, hot as fire,

Wide as England, tall as a spire,

Full of apes and cocoa-nuts

And the negro hunter’s huts;-

Where the knotty crocodile

Lies and blinks in the Nile,

And the red flamingo flies

Hunting fish before his eyes;-

Where in jungles, near and far,

Man-devouring tigers are,

Lying close and giving ear

Lest the hunt be drawing near,

Or a comer-by be seen

Swinging in a palanquin;-

Where among the desert sands

Some deserted city stands,

All its children, sweep and prince,

Grown to manhood ages since,

Not a foot in street or house,

Not a stir of child or mouse,

And when kindly falls the night,

In all the town no spark of light.

There I’ll come when I’m a man

With a camel caravan

Light a fire in the gloom

Of some dusty dining-room;

See the pictures on the walls,

Heroes, fights, and festivals

And in a comer find the toys

Of the old Egyptian boys.

.jpg)

English

English  Italiano

Italiano  Français

Français  Deutsch

Deutsch